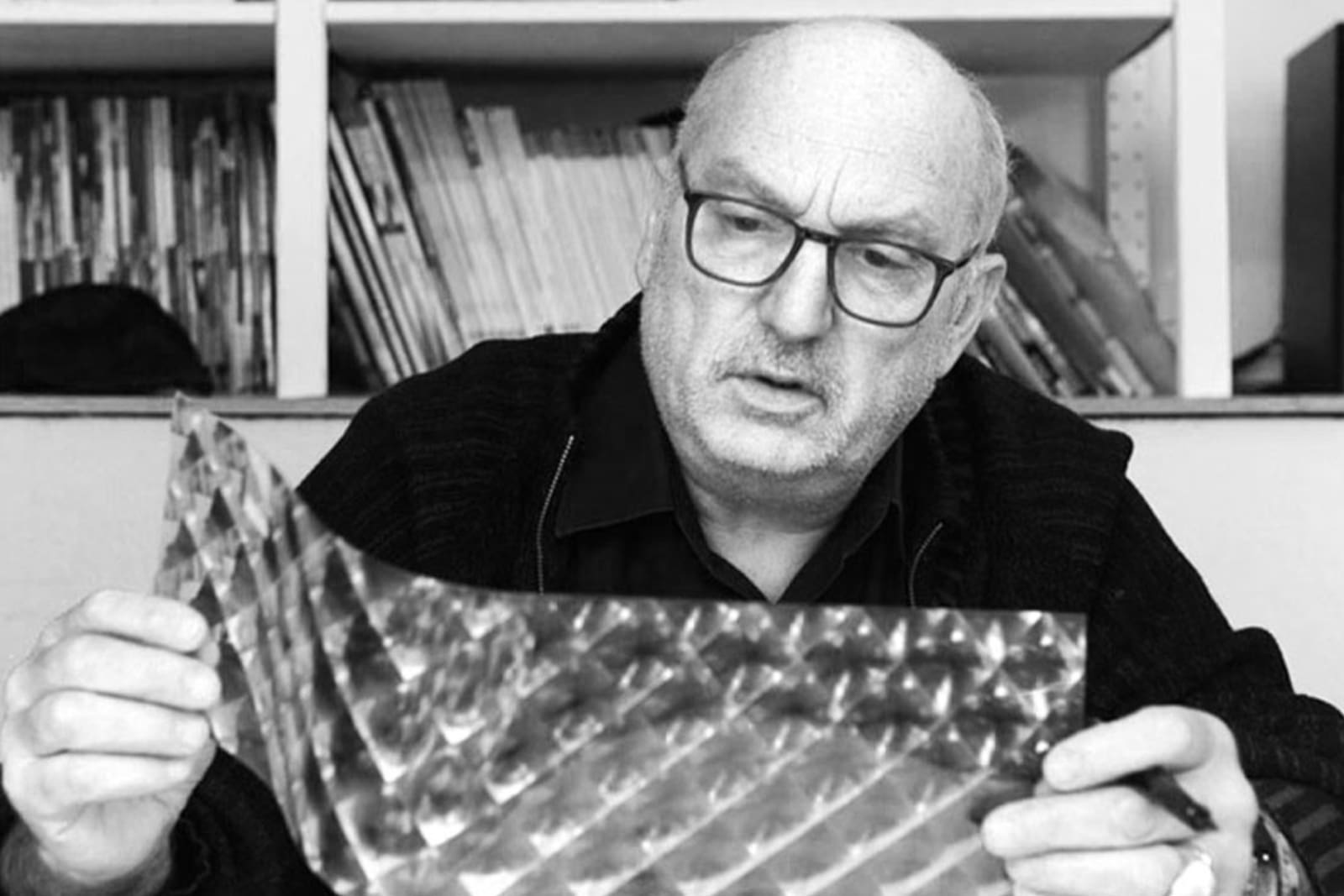

Yann Kersalé x Sammode

Yann Kersalé, an artist specialising in the use of artificial light, has left his mark on a number of iconic sites, from Fontevraud Abbey to the Grand Palais, from the docks at Saint-Nazaire to the Pont de Normandie, from the Vieux-Port in Marseille to the Jardin de la Divette in Cherbourg. It has also illuminated a series of contemporary buildings, including those designed by architect Jean Nouvel, such as the Philharmonie de Paris, the Agbar Tower in Barcelona, the Musée du Quai-Branly in Paris, the Lyon Opera, the Cité Manifeste in Mulhouse and the MUCEM in Marseille.

Inspired by glacial landscapes he has explored on his travels, Yann Kersalé has created a collection of lighting in 2018 called Lö. This collection draws its inspiration from his travels to regions such as Baffin Island in 2001 and Greenland in 2012, beyond the Arctic Circle, where he was fascinated by ice in all its forms. This fascination has enriched his image bank with numerous photographs of ice, which he considers to be ‘solidified light’, capturing and decomposing light in a unique way.

The first sketches for the Lö collection, produced in 2016, reproduced the photographs directly onto a translucent film to be inserted into the Sammode tube. Research then focused on the prismatic effects of the light reflected by the glass, leading to the choice of a reticulated film. The resulting luminaire has a unique duality: with two superimposed translucent films – one prismatic, the other mirror-like – it offers two distinct aspects. When switched on, it diffuses sparkling prisms ad infinitum, while when switched off, it reflects the surrounding environment.

The names of the luminaires in the Lö collection, such as Nilak, Qanik and Qinu, come from the Inuit language and evoke different states of ice.

As for the name of the collection, Lö, it plays on the semantics of the word “water”, symbolising the transformation of water into ice, and thus illustrates the very essence of these luminous creations.

Interview with Yann Kersalé

Christian Simenc: Do you remember your first contact with Sammode?

Yann Kersalé: I have a very precise memory of that moment: it was in the mid-1970s, I was a student at the École des Beaux-Arts in Quimper and my flatmate, an Irishman, had invited me to visit his country. On the ferry crossing to Dublin, I noticed the mood lamps and the light they gave off. I didn’t realise until a long time later that they were Sammode lights.

CS: When you were developing your first creations, you once again came face to face with the brand’s products…

YK: After studying at the Beaux-Arts, I started working with light. In 1981, I designed an installation for a blast furnace belonging to the Société métallurgique de Normandie, in Caen. It was called Siderxenon. Prior to the project, I visited the factory and spotted these extraordinarily strong pieces of equipment, made to withstand both bad weather and extreme conditions. Once again, they were Sammode luminaires. They were exactly the type of equipment I needed for my outdoor lighting installations. At the time, apart from modifying existing products or diverting industrial equipment, there weren’t many solutions. It was a revelation to me that light could be emitted from such a watertight object. The Sammode tube was an ideal device.

CS: Very quickly, you start working with architects. What do you offer them?

YK: Through my work with light, I generate a second life for the building at night. I offer the architects another vision, create a story, a light that is not only due to the functional light generated by the interior of the building. In fact, I create a sculpture with their building.

CS: Have you worked with Jean Nouvel in particular?

YK: Yes, as early as 1989, with the illumination of the Opéra de Lyon, an installation called Théâtre Temps. Then came one project after another, including the gardens at the Musée du Quai Branly. I imagine it will be a few more years before this moves from the stage of fundamental research to that of applied research.

CS: Are new technologies tools for artists?

YK: Yes, because they allow us to work with light in a sensitive way, and not just in a decorative or functional way. An artist has to appropriate them not in a spectacular way, but in a poetic way.

CS: Can light contribute to well-being?

YK: Absolutely: light is an essential element of life. It’s as important as acoustics or temperature. Light that is too aggressive is harmful. Well-being requires different types of light gradation, different ‘climates’. There is also, of course, a psychological relationship with light. Good light is like a good meal, a question of the right ingredients.

Download the brochure